To Lublin or Ljubljana

- May 16, 2017

- 10 min read

Last week, whilst I approached the “home straight” in terms of writing my next play, and sought to suck some fresh air in, and brace myself for the final sprint towards the finish line, this was the only question on my mind.

A change of scenery was desperately needed.

My momentum had been for some time in full flow, but as an OCD afflicted perfectionist, I appreciated the possibility of death by procrastination, and felt that some sort of divine sense of perspective was in order.

The problem was that, once again, I had left everything, quite literally, to the Lastminute.com.

The options before me, to book up, and pack up within the space of 24 hours were limited.

Lublin represented a less glamorous, perhaps more authentically Polish, side of the country with which I had not yet been acquainted. It was more untouched by Western liberal Imperialism, and more impervious to what John Betjeman might have called “inexpensive progress”, than Krakow – the city I have spent more time in than any other apart from London.

Ljubljana would offer an entry into a new country completely. In an era in civilisation in which authenticity has become fetishized as an increasingly rare commodity, it would be an even more unadulterated chip of the old Eastern Bloc.

I had heard mixed reviews of the latter city, but into the early hours of the morning of Friday 12 May 2017, the choice was taken away from me. With one automated click of a button, I received a message confirming my booking, much to my horror. And as I deliberated about whether or not to call their helpline, and explain that I had booked myself into a round trip to a city which I had no real incentive to visit, I glanced at the clock and decided the need for sleep before work the next morning was more important than my investment in time and money in a foreign land.

I texted a friend explaining the situation, and offered myself the rhetorical solace that it would only be for 24 hours, and it was the birthplace of one of my all time heroes – the philosopher and cultural critic, Slavoj Zizek – the Giant of Ljubljana and one of the world’s most vital and exciting thinkers.

On my way to the airport on Saturday morning, I had an argument with a lady with the same sort of emptiness in her eyes which I would hours later come to identify with the Slovenian people.

A sort of slightly prickly, schizotypic spiritual vacuity – a deadness even.

It seemed to me that Ljublana was not a Prague, or a Krakow, and it was almost completely inhabited by an interminably dull, lifeless and bankrupt people engaged in one big act. The Play of Sophistication.

Could the universe really work in such mysterious ways? Could my self-knowingly acidic putdown of an A8 migrant in my home city of London after her own self-indulgent show of arrogance, now be being paid for by a Saturday of miserable weather and miserable company alongside her country folk?

Slovenians it seemed, in a manner which is a typical function of the combination of small country + history of invasion by richer, more powerful neighbours, liked to distinguish themselves from the archetypal narrative of the slow emergence of Central or Eastern European nation from the dark overbearing shadow of the Soviet Union.

Once the victim of the might of the Austro-Hungarian empire, always the victim - although many identified with Italy, and very few with the USSR, they in fact seemed to possess no cohesive identity at all.

A South Slavic ethnic group with neither the cultural cachet of their Czech or the Hungarian counterparts, I observed that an inferiority complex was readily discernible with a concomitant pang of an ill-identified curiosity, hostility and jealousy of foreigners which ultimately converted itself into a longing for all things foreign.

I wondered whether this was what Krakow may have been like before 2004, and the tidal wave of EU handouts.

I thought about how the collapse of the Eastern Bloc had also really represented the collapse of Eastern and Central European identity, and how Slovenia appeared to have none – other than one which entailed chasing the shadows of the legacy of Western Europe.

I grew weary of the sea of stares of sexual desire from married women pushing prams with their husbands which they quickly translated into snide remarks of disapproval as soon as those husbands spotted them, with a smile and forced laughter.

I called a friend in disbelief when a Sales Assistant in a clothes shop alerted her colleagues to me, and followed me around in a daring dance of deception prevention (or shop lifting), and then said, quite deliberately so that I could hear it, in English, in her reply to something her colleague uttered by way of warning “Be careful of him. Nobody needs to die at work tonight.”

“You’re an idiot man.” My friend said. “She wanted your dick. You should have spoken to her.”

“Well. Maybe. I’m not sure even she knew what she really wanted from me.” I replied.

I thought about telling her, whilst I paid for the clothes, that the idea of me stealing some jeans worth £20 in Slovenia - given that I earned more in one week than the average Slovenian did in one month - was frankly beyond laughable.

As the red wine kept flowing, and my blood kept boiling, I thought about my play, and wondered why on earth I had ended up here.

These people. These sad, wretched people with their history of peasant slavery to Russia.

There are only a handful of countries which can be said to have enjoyed an epoch of genuine cultural greatness. Germany is one of those countries. Spain, Portugal, Italy, France, Greece and Britain are others. Slovenia is not one of them.

When my Spanish ancestors were producing the greatest literature in the known world, and discovering the unknown one – what exactly were they doing? Washing the assholes of Russian horses with their krpe most likely.

For a city so keenly and self-defensively aware of its own history, this was the truth of it. And of course the truth would hurt...

I laughed grimly to myself as the sky opened up and the rain began to pour down on a drab, dreary Saturday afternoon, drunk on a mixture of extreme arrogance and extreme self-disgust on account of my arrogance.

I crept onto a road just off The Triple Bridge over the Ljubljanica River in the city center to get back to my hotel room and away from it all, until I realised that this was a fitting metaphor for the weekend, namely a wrong turn.

I could no longer find joy in the novelty of meeting new people. I saw no good in other people any more. Everyone was just a sad, weak, helpless asshole fighting against the wretchedness of their legacy in this world. And recognising this fact made me the biggest asshole of them all.

I knew I was entering the darkest chapter of my life.

I had come in search of our Master, our Jesus, our Messiah – the one who more than anyone else retained that endangered ability to penetrate the truth, however horrifying it may be, and make sense of it by way of an offering of hope for humanity. But it had become tragically apparent that Zizek was the exception to the rule in Ljubljana, rather than the rule.

It was this latter thought which stayed with me at Ljubljana Jože Pučnik Airport on my journey home, as I read a collection of The Sonnets by William Shakespeare.

I had come to Ljubljana in search of the spirit of Zizek in the hope that it could spark my play’s end into life because I had followed one sort of prejudice – namely that the Slovenians are an intellectually superior, ultra-talented and multilingual race whose example we need to follow, but I had left with another prejudice identifying them as a strangely, small minded people in a small, strange city.

I looked up and saw a shabby, dishevelled and badly dressed man with a grey beard, hurry past the main waiting area to the edge of our gate. A small, strange looking man – one might say. His piercing blue eyes were crossed – resulting in a wild, manic expression permanently etched upon his face.

I calmly stood up, and followed his path very slowly, and fought against my guilt hard enough to take a photograph of him sitting in the corner of our gate, far away from the crowd, with my mobile phone.

After all Slavoj Zizek says that the biggest fear we hold in the 21st Century is the fear of harassment.

I calmly sat down and perhaps genuinely for the first time in my waking life imagined that I might be dreaming.

After about 5 minutes of cold, hard thought, I got up and went over to him.

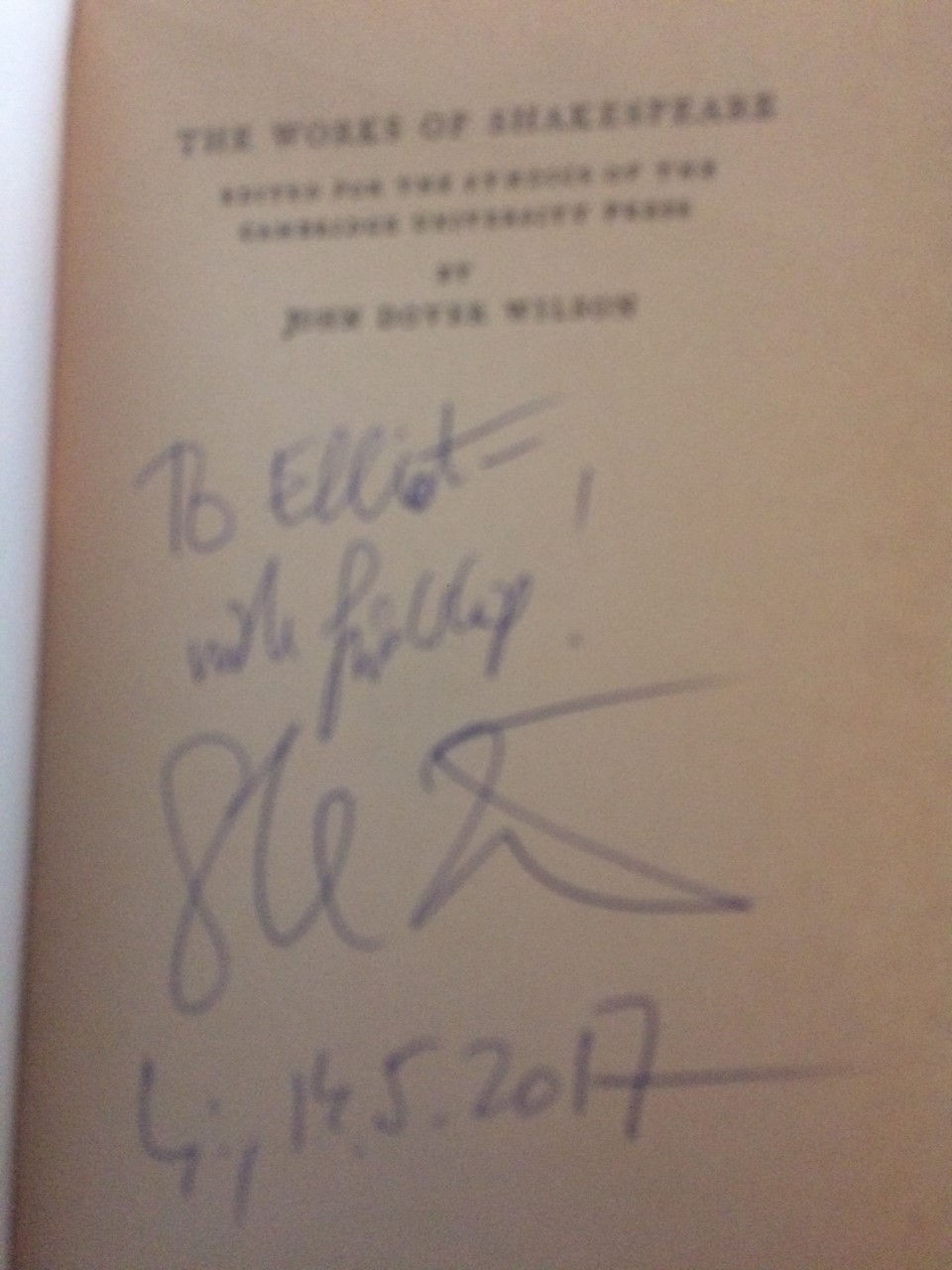

“Slavoj”, I said. “I really am sorry to do this, because I know you hate to do things like this but could you please sign my book? You are one of my all time idols.”

“Yah, yah.” he replied energetically in his wonderfully pronounced Slovenian accent. “Do you have a pan?”

“Er....no, no.” Having not even considered that I might need a pen for his autograph, I felt stupid and immediately sprinted away to a coffee shop, asking the lady behind the counter for one in a state of panic, in a bid to save his time.

Upon my return, my heart was literally thumping in my chest.

My professional life as a lawyer has with the years lent me a pretty unflappable sense of cool. I did away with nerves for the large part when I began to appear before judges in court, fully banishing any lingering fears I had of public speaking.

But here I was shaking like a child.

“I can’t believe it’s you. You’re the only reason why I came to Ljubljana.” I said hysterically. “I’m really sorry. I’m so nervous – I can’t speak.”

“Well then you came to the wrong place. I hate Ljubljana.” He replied in his idiosyncratic deadpan manner.

I laughed hard – perhaps demonstrably over-enthusiastically.

“What’s your name?” he asked me.

“Elliot I replied.”

“Eliot? As in T S Eliot?”

It then took me around 4 guesses to spell my own name. Once he finished signing my book, I offered him my hand, and said: “You’re an inspiration to me. You’re a genius!”

“Come on. Be serious!” He responded with a friendly but paternalistic Soviet tone of hyper-macho modesty. I suspect that Mr Zizek probably hears this type of comment a lot, and as he did look awfully busy with his laptop on his lap, he may have been rather keen to bring this conversation to an end.

When I returned to the main waiting area, I was shaking for around 30 minutes, and had to smoke two cigarettes in the smoking booth (a strange deathly looking feature of some Eastern Bloc airports which resembles a glass prison cell in which cigarette smoke is sucked down an air vent) in order to compose myself.

At this juncture, and in this context, it would be right to point out what Mr Zizek would likely make of this story – assuming that he would even give it a second of thought.

Perhaps he would flag it as an example of the “worst type of prejudice” marking relations between West and Central and Eastern Europe today, namely the latent condescension tied up in the idea of the West seeking intellectual salvation in the East.

" On the one hand, we accept that they are intellectually superior to us. On the other, we take satisfaction in the knowledge that this is only because their history of economic and material destitution means they have to be intellectually superior. Because we are wealthier."

However my own retort to that imagined criticism is that such a view would be mean spirited, and most likely to a large degree circular.

After all, once the idea of Western Liberal prejudice towards the Eastern Bloc states (the idea that we view them as exotic zoo animals) becomes too deeply engrained in the latter, this must inevitably result in its own bias and condescension amongst people from those states towards the West.

“They think that they are better than us because they have more than we do....” is very easily transformed into “They do not deserve to have more than we do. Those stupid rich, lazy Westerners.”

And in the end, let us be honest, that could explain why a smartly dressed obviously foreign looking man might, in certain conditions, meet such a hostile reaction in the first place.

I did speak to some Slovenes who had spent at least half of their lives abroad, and it was interesting that they all told me that they did think Slovenians were generally hostile towards foreign people and that denial of this was basic dishonesty.

In the end however, the question which resonates with me is the meaning of that chance meeting.

What are the odds of such an encounter in a context like this one happening?

The cynical reply might be “Meh. You are reading too much into it. Ljubljana is a tiny city. Zizek is there often. So you met him at the airport. Big deal.”

But Freud himself was a cynic. And Freud says there is no such thing as a coincidence.

You start off with the fact that I clicked that confirm button on my computer by mistake, then consider that I could have cancelled, and then consider the likelihood of my return to London from Ljubljana coinciding with his, and the branch soon becomes a tree, which soon becomes a forest.

The odds of this happening were no lower perhaps than the odds are of my winning the jackpot on the lottery this week.

Anyone who knows me, and by this I mean, really knows me, will know that I hold certain spiritual views about the universe which could very vaguely be described as esoteric.

I could talk about how Zizek was constantly on my mind all weekend, and how my consciousness manifested him. I could talk about the illusory, enigmatic nature of life and how it is little more than what we dream it to be.

But this is not the context in which to do it, and these are not ideas that should follow the image of the assholes of Russian horses being washed by serfs.

In the end, suffice it to say that the mind is a very powerful thing, and we really do create our own reality.

Now to get on with finishing that play....

Comments