The Master: A Film With Two Faces

The Master: A Film With Two Faces

A Review of Paul Thomas Anderson's little seen and lesser understood 2012 masterpiece.

The Elephant in the Room:

In one of the most legendary encounters between two philosophers of the modern age, in 1911 Bertrand Russell, who had just authored volume one of Principia Mathematica, and was by then a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, was having his tea when a precocious and brilliant young Austrian philosophy student suddenly appeared and challenged the reigning champion in a series of philosophical discussions.

Russell was initially unimpressed by the young upstart – Ludwig Wittgenstein – who would of course also go on to become one of the greatest philosophers of the last century, and complained “He thinks nothing empirical is knowable," when the Austrian refused to admit, for example, that there was not a rhinoceros in the lecture room, even after Russell had checked under all the tables and chairs.

I often imagine this conversation, which was to become the springboard for a meeting of two very great minds, when talking to friends who have just watched Paul Thomas Anderson’s hugely acclaimed and little seen 2012 film The Master upon my recommendation.

After all this was the film of which the world’s foremost film critic (without question an artist in his own right and someone for whom I have an unreserved amount of respect) Roger Ebert said:

“Paul Thomas Anderson's "The Master" is fabulously well-acted and crafted, but when I reach for it, my hand closes on air. It has rich material and isn't clear what it thinks about it. It has two performances of Oscar caliber, but do they connect?”

Following up 2006’s “There Will Be Blood”, a film which is widely accepted to be the best film of the past decade, always seemed like a hapless task, perhaps analogous to the remit that David Moyes inherited at Manchester United FC following the retirement of Sir Alex Ferguson.

Quite simply, one had to deal with the legacy of an act that was impossible to follow.

Indeed even the film’s greatest advocates are forced to frame the glowing admiration in a context which accepts that the film is a mystery. To call The Master an “enigmatic” film would seem to be the closest thing there is to the understatement of the century.

This complete unwillingness to give the viewer anything resembling conventional catharsis is the quality of the film which coloured its most critical reviews. And there were plenty of critical reviews too. Perhaps more than any other film of the past decade, The Master is one that divides opinion.

“Call The Master whatever you want, but lobotomized catatonia from what I call the New Hacks can never take the place of well-made narrative films about real people that tell profound stories for a broader and more sophisticated audience. Fads come and go, but as Walter Kerr used to say, "I'll yell tripe whenever tripe is served.”" writes Rex Reed of the New York Observer.

“The Master has become a contest between two gifted actors trying to shout each other down. The commitment to their roles is impressive, but it's tethered to a weightless, airless movie, a film so enamored of itself, the audience gets shut out.” is what Rene Rodriguez of the Miami Herald had to say, widely echoing the most common afterthought of the negative end of the spectrum of critics’ views, namely that the film was staggeringly well acted but ultimately pointless to the extent that it lacked any linear sense of direction.

Conversely The Master was the film of 2012 according to The Guardian, Rolling Stone, Sight and Sound and the Village Voice, finishing an overall second place on review aggregating site Metacritic.

“But the neg-heads say, "I don't get this movie." Talk about it, people. See it again. Pry into it. Discuss your issues with friends. Argue. Debate. That used to be what movies were about till the multiplex turned our brains to mush.” was what the first place prize looked like on Rolling Stone’s end of year poll - even the most ardent followers of the film in unanimous acceptance of its elusive heart.

And to give a flavour of just how elusive that elusive quality is, contrast these two 5 star reviews from The Guardian. “Paul Thomas Anderson's meditation on Scientology starring Joaquin Phoenix is an utterly absorbing psychological drama of marginal lives.” writes Peter Bradshaw in a September 2012 review whereas in a November 2012 review with the same newspaper the same critic calls The Master “a brilliant and sad dissection of postwar America”, stating that the film “is brilliant, mysterious and unbearably sad, in approximately that narrative order” in a review which argues that some of the criticism directed at the film was a manifestation of the apprehension that reviewers felt at the idea of labelling two consecutive films by the same director as masterpieces.

So, the obvious and quite natural question, is which one is it? Is it a film about American society or two people? Can anyone, even those like myself who have ranted and raved about this film for the best part of 2 years, arrive at a definitive conclusion about what The Master is actually about?

The answer to this question according to everyone I have spoken to is a firm and unreserved “no”.

The Plotline:

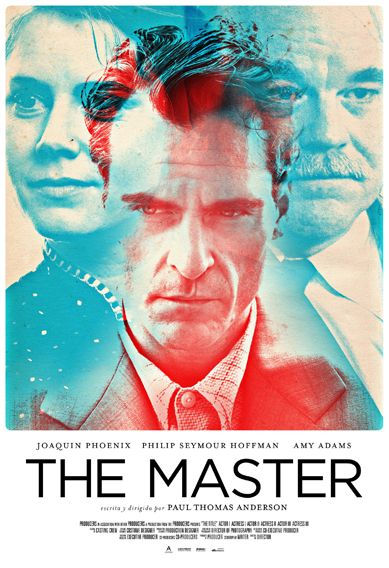

Let’s get this out of the way. The Master is discernibly a story set in the recent past about a traumatized and mysterious WW2 veteran turned drifter (Freddie Quell) played by Joaquin Pheonix who runs into the charismatic leader (Lancaster Dodd) of a cult called The Cause, played by the recently deceased Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Dodd tries to apply the methodology of The Cause to Quell without much success, much to the disapproval of his wife Peggy (Amy Adams). Although each comes to represent (for whatever reason) the most important relationship in the other’s life, it becomes clear by the film’s conclusion that there is a gap between the men which can never be bridged.

And that’s it.

That is all that one could definitively say happens in a film that runs for over 2 hours.

The Joaquin Pheonix Problem:

Let’s be technically very accurate about the reception that Joaquin Pheonix received for his portrayal of Freddie Quell in this film.

This is not only interesting but actually I would argue, essential, to fully understanding the legacy that the film looks likely to enjoy in years to come.

To put things chronologically, the first reviews were rave ones.

Pheonix was the runaway tip to win the Oscar for best performance with most film reviewers. Then, having received the nomination, Pheonix in his own characteristic fashion slammed the Oscars as “bullshit”, tore apart his own performance in the film and alienated himself from audiences and critics alike with a series of conferences and interviews ranging from bizarre to truly baffling. In the end Pheonix lost out to Day Lewis (Lincoln) and the critical reception turned decidedly frosty.

Tom Shone, the Guardian's film blogger wondered in 2012 whether Phoenix's performance was "too nuts even for the academy", stating "The performance has been a tough sell. The question mark over the performance for me is that it bordered on being a little bit exploitative – Phoenix's psychological unravelling on screen. His best performances have always bordered on: 'How much of this is acting and how much is he going through a breakdown?'"

We are undoubtedly currently witnessing something of a Golden Generation of Actors and Actresses in Hollywood (Jessica Chastain, Jennifer Lawrence, Christian Bale, Leonardo Dicaprio).

I can imagine how Ryan Gosling would have handled the Freddie Quell character, infusing the mysterious and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder addled WW2 veteran with a propensity towards random explosions of violence and an alcohol problem of quite monumental proportions, with enough film school ticks and stutters to make the character believable but at the same time retaining enough Ryan Gosling charm and sex appeal to give the character the necessary gloss for a Hollywood audience.

Perhaps Michael Shannon would have bottled things up ominously before using his darkly magnetic acting powers to erupt in one transcendent moment of cathartic rage.

But instead what we actually get is Joaquin Pheonix loosing himself in a performance so completely that in the end it is frankly just weird.

The same Joaquin Phoenix who came to public attention in a 911 phonecall to dial an ambulance on the night his brother River died of a drug induced heart attack.

The same Joaquin Pheonix who just two years earlier had confused fans with “I’m Still Here” a documentary about his decision to quit Hollywood and relaunch himself as a rapper – complete with scenes of cocaine fuelled sex with prostitutes and a woman defecating onto his chest.

From playing a masturbation addicted teen in 1989’s Parenthood to an incestuous Commodus in 2000’s Gladiator and the drug addicted original “Man In Black” himself in 2005’s Walk The Line, Pheonix has a long and rich history of doing freakish a little too convincingly.

He is without a doubt the most “out there” actor in Hollywood.

Pheonix has been something of a victim of his own talent as an actor.

The first time I actually saw him was in 1995’s To Die For. I had heard great things about his performance (even at 12 years old) and upon first viewing of him as a horny teen who gets to bed Nicole Kidman in exchange for murdering her husband, I hated him. I simply could not bear to watch his jailed character at the film’s conclusion describe how he cannot wait to sleep at night so that he can dream of her whilst masturbating, simply because his reptilian facial features and creepy manner of speaking made the character’s grotesque qualities seem too real. I only learned to appreciate his performance when I was old enough not to feel any jealousy towards him for the fact that his character shags Nicole Kidman.

It was equally interesting for me in 2012 to read the comments of people on Youtube who apparently disliked the film. “Joaquin Pheonix is so creepy in this film that I couldn’t enjoy it” writes one turned off spectator. She sounded as young as I was when I first saw To Die For, so fair enough. She could be forgiven.

But it turns out that despite many professional critics lauding this performance as one of the all time great performances in Hollywood cinema, to such an extent in fact that Pheonix rocketed up to a Top 5 place with many magazines in Best Actor Ever lists on the strength of it, there were others who had the same problem. “Phoenix's performance is one of such wild, intense abandon that it is not to be believed, and this, in fact, was my problem as The Master sailed into its momentum-less second hour.” (Steven Rea, Philadelphia Inquirer).

The reception therefore followed a certain inevitable type of logic. Starting from rave reviews full of admiration, they gradually turned into reviews full of distrust.

Isn’t this really just a very messed up guy playing a very messed up guy? Should we even be calling this acting?

Right from the word go, it is obvious that Pheonix’s performance is not going to be pretty or particularly easy to watch. We watch him simulate sex and masturbate on the beach without much dialogue during a prolonged opening scene, not dissimilar to There Will Be Blood’s beginning.

When we first hear him speak, it is pretty obvious within seconds that we are watching perhaps the most technically gifted actor of his generation.

One thing that Pheonix has gone to great extremes to make clear is the physiological damage that war and spiritual and emotional starvation have done to Quell. His body seems bent out of shape and lacking symmetry - with Quell walking and moving in a quite literally unbalanced animalistic fashion. Pheonix has visibly lost a lot of weight for the role, stripping his face down to jagged angles, blade like cheekbones and wrinkles reading like a road map to failure. He has also made use of his legendary scarred cleft lip, seemingly bending his whole face lopsided to render his speech a barely intelligible snarl of strings of words without punctuation.

It is a performance that is disjointed, unhinged and often as ugly as hell - and the overall effect is unsettling to say the least.

Yet it is also a performance that is the product of meticulous study. The Master is essentially a period drama and Pheonix is not so much emulating the onscreen greats of that era (Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift) who often seemed to specialise in playing damaged goods as much as he is channelling them directly.

And therein lies the paradox of his performance.

Although Pheonix is giving the greatest acting performance in recent Hollywood memory, it feels as if in taking on the role of lost soul Freddie Quell, he has finally found the role closest to his true self and in effect is just playing Joaquin Pheonix.

Hollywood audiences finally caught a glimpse of the real Joaquin Phoenix in this film. And it turned out that not everyone liked what they saw.

This problematic nature of the art/life distinction with Pheonix in the film manifests itself in almost every discussion of The Master.

Read for example the following blog, where the amateur reviewer is not quite sure (somewhat amusingly it must be said) whether to applaud or criticise Pheonix for playing an alcoholic in a way that he always seemed drunk:

“I have to say I enjoyed Joaquin's performance. But I can't pretend I don't see the fact he wasn't very realistic, nor believable. He has the opposite problem than Washington has, actually. While Washington didn't seem drunk when he should, Phoenix seemed drunk when he shouldn't. It seemed to me as if he was drunk throughout the whole film, in every single scene, without an exception. And I doubt if he should do that.”

http://moviefilm-moviefilm.blogspot.co.uk/2013/02/best-leading-actor-2012-joaquin-phoenix.html

In fairness, Pheonix did not exactly do himself any favours in this regard either. In what could have been regarded as one of the greatest acting comebacks of all time, Pheonix immediately pretty much rubbished all critical praise directed towards him, and refused to discuss the role in any meaningful way, thus breaking down the art/life distinction further.

At the Venice Film Festival, he responded to all questions about the challenges of playing an inarticulate, drunk lacking any basic social skills by appearing inarticulate, drunk and lacking basic social skills whilst an apologetic Paul Thomas Anderson and Phillip Seymour Hoffman laughed nervously and tried to smooth things over.

In the end only two questions linger in relation to Joaquin Pheonix in The Master. 1) Was he juiced during the making of the entire film? 2) Is he the greatest living actor of our generation?

The answer to both questions is probably "yes".

Pheonix is possibly the last actor of his type in Hollywood, after a long illustrious line taking us from the likes of Brando to De Niro and Al Pacino. An actor who takes his art to the edge.

Addendum: I first started writing this review before the death of another true acting genius Phillip Seymour Hoffman. I was minded to completely scrap my focus on Pheonix in tribute to the great man who was also nominated for an Oscar for his turn as Lancaster Dodd.

In the end, the honest truth is although Hoffman is (quite literally flawless) he just so happened to come up against undoubtedly one of the top 5 acting performances in Hollywood history and perhaps a contender for the greatest ever.

Suffice it to say that people who try to compare Hoffman to other great actors face an impossible task. He has been phenomenal in Magnolia, Capote, Boogie Nights, Punch Drunk Love and many other films. An actor of unrivalled humanity and generosity, I am not sure I could compare his acting style to anyone. He was simply too unique.

Unwrapping the Puzzle:

In a very negative review of the film, entitled “”The Master” is a Failure Disguised as a Masterpiece.”, Louis Plamondon, referring to the critics who lavished praise on all parties involved, says “On the other hand, none of them have been able to agree on what the movie was about as each of them offered their own patched up explanation of why we should care for The Master. Almost all of them called the need for a second viewing, thus bearing the responsibility of the film’s confusion on their shoulders.”

http://filmschoolrejects.com/reviews/tiff-2012-review-the-master-loupy.php

The interesting thing is I do agree with his “Emporer’s New Clothes” analysis, in theory. To simply state “You need to watch the film a second time” in response to a question about what makes this film so great should ordinarily be no answer.

As it happens I also think he is right about the undue influence of Hipster culture upon critical assessments of modern art. Let’s face it, rock music died a lonely death a long long time ago and multicultural societies across the globe are more notable for the staggering level of conformity amongst their people rather than any palpable sense of freshness.

But although I agree in theory, I do think that there is something that has been missed by those who hated the film (and the reaction is always one of either love or hate).

I could take about Johnny Greenwood’s haunting, eerie and sometimes chilling soundtrack, its strange time signatures a constant reminder that there is something not quite right about what you are watching. Or Anderson’s stunning visuals which are often breathtaking.

But more than anything else, I think I have an appreciation for the bravery of Anderson in trying to convey a concept on the big screen which is too abstract to be explained or fully put into words.

"Ok fine" my brother said upon being forced to watch the film by me a few months ago. But what is that concept?

Well perhaps the best discussion of the many possible readings of the film is this one:

http://www.vulture.com/2012/09/what-is-the-master-really-about-five-readings.html

Bilge Ebiri, by way of very brief summary, sets out 5 potential and perfectly feasible readings of the film:

The Search for A Family and Stability; pretty self-explanatory although Ebiri interestingly compares the way Hoffman’s character Dodd serenades Pheonix’s Quell at the end to a parent singing a lullaby to a child – “the most domestic and familial of actions turned into something terrifying and strange”. Very fine analysis I must say.

The Politics of Cults, and the Cults of Politics; “Freddie is, ultimately, symbolic of the common man who joins a cause not because he believes in it, but because it will have him.”

Doubles; “If the processing/auditing that the Master encourages is designed to shed oneself of the negative emotions and troubles of our past lives, consider the possibility that Freddie might actually be, at least on a metaphoric level, one of Lancaster Dodd’s past lives. (Which makes the oft-stated question in the film of where they might have met a more haunting one.)” It is a mind boggling possibility but a plausible one. Could Freddie Quell simply be the troubled past life of Lancaster Dodd? As Ebiri makes clear, the focus of The Cause on regression therapy would seem conducive to such a metaphor.

Post-war ennui; This is more a subtextual point than the point of the film. But there is no doubt that Anderson does try to elucidate the “hidden history” of the Second World War, namely the fact that a whole generation of young men left for war only to find that there was nothing really waiting for them at home upon their return therefore suffering a sort of cultural dislocation which was never properly documented.

Acting; One could forgive people for feeling slightly angry or cheated even were they forced to sit through such a cryptic puzzle of a film only to learn that it is really about the collision of two acting styles. But if any director were to pull such a stunt, let’s face it, it would be Anderson. “it’s perhaps notable that Phoenix’s performance seems to represent the tormented, physical acting styles of the latter half of the twentieth century (the Brandos, the Deans, the Clifts) whereas Hoffman’s acting seems to hearken back to the controlled, elusive manner of the previous half (many have described his turn as “Wellesian”).”

So what do I think? I have never been particularly known for sitting on the fence when it comes to opinions about art. And so I will throw my own hat into the ring.

For what my money is worth, I think the most apposite review of the film that I have read so far is Emma Dibdin’s excellent write-up for Total Film who states “Anderson has made the boldest American picture of the year. Its strangeness can be hard to process, but this is a shattering study of the impossibility of recovering the past.”

The Master is essentially no more and no less than a film about something we all experience – man’s troubled relationship with nostalgia.

The Man With No Past

Consider the following:

The film deliberately opens in the late 1940s. Ok, this may follow from the WW2 backdrop but this is not ostensibly a film about war. Anderson seems to have picked a time in the very recent past. Recent enough for us all to almost have an out of shot memory of it but not quite within living memory for most. The effect is to render us in a setting which is familiar yet somehow strangely alien. Hold that thought.

When we first meet Freddie Quell properly, he is being interviewed by an armed services man who seems to be an acting mental health professional. He questions an obviously traumatised Quell about two incidents. 1) A “crying episode” upon reading a letter from his old girlfriend Doris Solstad and 2) A vision he has apparently had about his family in the past. A clearly emotional but barely comprehensible Quell tries to explain both incidents although his voice breaks and he comes close to tears on both occasions (with Pheonix launching the film off with some of the most emotionally staggering acting you will ever see). He explains (with his bizarre habit of laughing at inappropriate times) that incident 1) was brought on by “what people in your profession call “nostalgia”” but becomes visibly uncomfortable when questioned whether the girl was his “sweetheart.” He objects to incident 2) being described as a vision. “No sir, it wasn’t a vision. It was a dream.” When he reluctantly explains that the dream was about “my mother, my father and me...back home...sitting around the table...with drinks...laughing [or loving]” he again comes close to tears before laughing and saying “it just sort of ended there.” It is later revealed that Quell’s father is now dead and his mother is psychotic and in a mental asylum.

Hoffman leads The Cause with ideas that he teaches to his followers and describes fully in books he writes. One of the basic tenets of this fuzzy and barely articulated belief system seems to be the idea of past life regression – recalling memories from before birth – as a beneficial and healing process.

When Dodd first meets Quell, Dodd says “You seem so familiar to me.” One of the film’s most haunting recurring motifs centres around the idea that Dodd and Quell have in fact met before in a past life, pun very much intended.

When Quell first leaves The Cause (by riding off into the sunset on motorbike) it is unclear how much time elapses between this interval and his final showdown with Dodd in England. Months? Years? Everything seems to operate in a dream like sequence of events, with it being unclear what comes first and how it all fits together.

Quell’s first stop after riding off is to his old neighbourhood to see Doris Solstad. In a very Brando-esque turn that is again meticulously well acted and often difficult to watch, he learns from her mother that she is no longer there but is now married and has two children. It is again unclear how long Quell has been away from his neighbourhood and tellingly he did not seem to know Doris’s age when he did know her, having to calculate it backwards by learning that she is now 23.

In a blistering scene, a brilliant Laura Dern questions Dodd about certain changes he has made to the prescribed methodology of The Cause, having seemingly shifted from an “I recall” past lives position to an “I imagine” one. When Dern questions Dodd about this, asking whether this would not have far reaching implications for the entire premise of the Cause, Dodd snaps furiously before stating “I recall allows for a more imaginative process.”

When Quell travels to see Dodd in the UK, he does so, apparently, as a result of having dreamed that Dodd had beckoned him over.

When Quell finally asks Dodd where and how they met (during that final showdown scene), Dodd claims that he used the Cause's methods to "go back" and uncover that the pair had first met during past lives. They had both served in war, aiding the French fight off Prussian forces. Quell looks at Dodd despairingly and shakes his head in some form of acknowledgment that this is a badly disguised lie about their shared history in order to win him over.

So there you have it.

Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins once famously sang “Time is never time at all, you can never ever leave without leaving a piece of youth.” It is precisely this philosophical conundrum that The Master, perhaps more than any other film (apart from Memento), continually drives at.

How much of the past do we see in rose tinted spectacles? How much do we imagine as opposed to recalling? This uneasy interaction/relationship between man and time permeates the substance of The Master – a film about an irreparably damaged’s man tragic failure to reconnect with his past and therefore find meaning in life.

To that extent “The Master” is neither Dodd nor religion. The Master is simply the structure we put in place (whether it be family, religion or politics) to give our lives some meaning.

It has to be noted that The Master is not without its flaws. The most obvious is the film’s very heavy dependence upon the final exchange between Dodd and Quell to give the film some sort of emotional resonance. I would argue that without this final showdown between two characters who come to depend on eachother although they are so fundamentally at odds, it is not just the case that you would not have an uneven film – you probably would not have a film.

It is ironic then that in such a cryptic film, its crowning achievement adheres to the basic formula of the tearjerker. The last final goodbye between is expertly set up by a symphony taking us from Quell dreaming of being called to England by his old friend Dodd in a cinema, across the Atlantic and then finally to the huge foreboding room which frames their final encounter.

Dodd’s wife Peggy (played brilliantly by Amy Adams) firstly shows some maternal instincts by telling Quell that he “looks sick” and then admonishes him for “not being able to take this life straight” and storms out of the room declaring “This is pointless. He isn’t interested in getting better.”

And then you have that goodbye.

The one moment in the “Free to Go” scene which I found the most troubling is also the one moment which to me confirms Pheonix’s rightful place as the greatest living actor of our generation.

Undoubtedly improvised in order to tug at the heart strings, when Pheonix and Hoffman’s characters at first hesitantly but then warmly hug each other, Pheonix then wipes the shoulder of Hoffman’s jacket as if to suggest his own inferiority, worthlessness or dirtiness to a very well groomed and imposing looking Hoffman in his grandiose surroundings.

He then sits down and polishes the table with his sleeve. Make no mistake. Pheonix here knows exactly what he is doing. He has also withered his face down even further to signify yet more spiritual and physical devastation. But that is the moment that always gets me.

I am left with a lingering question? Is Freddie Quell’s story really just one of a vulnerable person – a mentally unwell man?

Remarkably upon a cursory Google search, I found that others had asked the same question and it turns out the answer is hardly a convincing and unanimous “yes” :

http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/headshrinkers-guide-the-galaxy/201305/psychoanalytic-look-the-master

In a strange way, Freddie Quell’s character has to be admired for his resilience to forge his own path, for his steadfast refusal to settle down with The Cause or serve “any Master” despite the destructive side-effects of such a choice.

Dodd finally serenades Quell with an utterly bizarre, possibly homoerotic and wholly cryptic rendition of “(I'd Like to Get You on a) Slow Boat to China”. Nothing is spelled out. But Anderson seems to be suggesting that even in this undoubtedly poignant goodbye, there is a level of parity between two characters who have both made different but equally difficult choices; one to lead the way as oil slick salesman with a system of belief that he can barely believe in himself, and the other to go it alone as drifter and wildman onto a probable premature and painful death.

The film therefore suggests both that constant travel/motion without any sort of anchor becomes its own sort of stasis (its own prison) (as exemplified by Quell) and that rigid societal structures and systems of belief entail very real limitations on individual freedoms (as exemplified by Dodd).

It is a real spell binder of an ending and one whose meaning will be debated for years to come.

Psychologists are often in agreement that depression occurs when we fail to construct (or imagine) a positive and meaningful future. Freddie Quell’s own future points only towards a past that perhaps never really existed the way he has imagined it.

So when Ebert says of the film, “when I reach for it, my hand closes on air.”, he perhaps unwittingly has summarised the film’s true message. The past is intangible – something illusory and never again capable of being experienced.

Because Freddie Quell's childhood and adult lives have been littered with trauma, his past remains inaccessible to him - something he detaches himself from - and he has become a man without a past. This means that in one way he is "free to go" as he pleases, without anything to anchor him, but in another way he is fated to wander the Earth aimlessly.

His freedom from his past therefore comes at a terrible cost - and this is why Quell crosses the Atlantic, and follows Dodd to England, to see if there is any truth in the idea that they did meet in a past life.

Dodd, in contrast, is busy inventing his own narrative reality - happy even to use his imagination with regards to his past - instead of recalling as Quell tries not to - yet he too pays a price - namely the sacrifice of his free will.

The Master may indeed be a film which requires multiple viewings to fully appreciate its abstract propositions. But however many times you see the film, it will leave you with the same question.

What ever did become of Freddie Quell?