Man Is A Port, Not An Island: A Memoir of My Visit to Porto

Somewhere, although I know not where, I have a British book on one of my bookshelves called “Pass the Port”, which is no more than a collection of only occasionally amusing “after dinner” stories that have been recounted by the rich and the famous.

Port – for so long a staple of British upper class social (and antisocial) life – which has indelibly coloured the literature and the etiquette of British life – has today become an indispensable reference point in the imagining of British authenticity, the stuff of cliché and even sometimes pretension.

“Silver and ermine and red faces full of port wine.” John Betjeman

Graham’s Vintage Character Port, the name previously given to Six Grapes by merchants in the UK, is known to have been a personal favourite of Sir Winston Churchill - as favoured indeed as his beloved late Victorian imperialist racism and fantasies around the potential uses of chemical weapons.

On 21 May 2015 Washington Tasting Room Magazine reported the breaking news that one Michael and Cindy Jacobsen had recently hosted a “Downton Abbey” themed wine event among friends at Plateau Wines, the city’s newest wine bar and wine store, at which (needless to say) Port was served after dinner.

So far, so good, so "British"….

We must however not allow this opportunity to elude us. If the political climate of Brexit Britain has gifted us with anything, it is the opportunity to re-evaluate British history through the prism of its role in Europe.

To a large degree Brexit has by default of the mechanics of its laboured and abortive realisation as a legal and political outcome, urged the British to change their subjective vantage point.

For perhaps the first time since the disintegration of the British Empire, the question is not so much “What must we make of those Europeans?” but rather “What must those Europeans make of us?” placing us in an interregnum of political rule and an abyss of discontinuance.

With the British currency now in rapid decline (in every sense of the word), the opportunity is there to re-think.

I once had a conversation with an older member of my gym, an ebullient Geordie man with a full head of silver hair and a twinkle in his eye, who recounted the sad story of his mother’s final years in Albufeira in the Algarve.

“She had Alzheimer’s but it took a long time for us to notice like.”

He had gone to visit her once in the summer. Somewhat alarmingly she lived alone in a high spec but largely anonymous new build apartment.

He had noticed that she had very few dishes in her kitchen and even those had seemingly been stored away for a while.

“You’ve not been eatin’ nowt Mam!!”

He had taken her shopping. At least he had taken her to the nearest supermarket and given her 40 Euros to buy food with whilst he perched on the fence outside to smoke a cigarette.

She had come out seconds after. He was nowhere near finished with his cigarette.

“Have you got everything Mam?”

“Aye Son.” She replied.

He checked her shopping bags and found nothing but 4 bottles of Vodka.

“What must those Europeans make of us?”

For a nation with such a deeply entrenched sense of self-importance, the British people are often found to be surprisingly lacking in good taste.

When I was last in the Algarve, I made sure to avoid Albufeira.

When Douglas Sutherland wrote in his 1984 tongue-in-cheek satire of the Englishman out of his element “The English Gentleman Abroad”, that “the English Gentleman invented abroad”, that sentiment would have been appreciated, albeit perhaps too lovingly and with an air of defiant although ironic self-congratulation, by his countrymen as a satire of British self-importance and self-delusion.

Today it might instead be taken as a literal statement which commands universal approval.

This strange political attitudinal shift driven by the rise of national populism is readibly discernable not only in the colonial amnesia which has spread like wildfire in the modern British psyche but in the pathological reluctance of many British people today to appreciate the factual reality and longstanding influence of the world around them.

The paradoxical effect of this shift is that arguably the Britain of a few decades ago (despite its proximity to the British Empire and deep rooted social rigidity) was somehow more in tune and in sync with this factual reality than the Britain of 2019.

Alec Clifton-Taylor’s book “The Cathedrals of England” (first published in 1967) is totally apolitical in its acknowledgement of the debt that British architecture owes to Europe. He writes “But as builders the Anglo-Saxons do not seem to have been very skilful.”

Does anyone know any Polish builders?

Perhaps when British people were somehow more comfortable with and confident in their own identity and place in the world, they were also more receptive to truth.

I recall a conversation I had with a friend in London upon returning from Brussels and commenting that the latter city often paid higher wages than the former (the average annual salary in Brussels at the time of writing is about 64, 000 Euros).

My friend replied that this was simply impossible. I asked her what exactly she meant by “simply impossible” and explained why people in London were indeed often less well off financially than those in several other European cities.

She looked at me as if I had just diagnosed her with cancer.

These were the thoughts that occupied my mind whilst I sat in a 400 year old building by the Dom Luis I Bridge in Porto’s Ribeira last weekend and washed down some truly outstanding tender and richly flavoured bacalhau com natas with another sweet berry flavoured glass of velvet Port wine.

Porto is not so much a city that has to be seen to be fully experienced as it is one that has to be tasted and felt.

As you stroll by the riverside, the Dom Luis I Bridge arches above you, rising from both banks of the Douro river and is reflected as a perfect oval upon the river’s glistening breathing surface, transporting you from famous old wine cellars to elegant riverside cafes.

You see the colour of the houses all around you and the sun makes leafy shadows and patches of sunlight on their stunning designs.

You become aware of the smell of the Potuguese tapas of sizzling seabass, shellfish and baked octopus.

It is a colourful and aromatic experience as my riverside seating (some of the finest in Europe) gives me a spectacular view of the Douro at the bottom of a promenade of old pastel-hued houses and hole-in-the-wall taverns.

The picture teems with activity although the atmosphere is one of serene bliss.

If you look up, closely, above the zig-zagging, spiralling cobbled streets, you see that these old houses are still lived in, as people have hung their clothes to dry out on their balconies.

The Portuguese are on the whole a fine people – often physically and socially charming, and, in the North, usually very well dressed. Their easy, quiet, subtle sophistication is easily missed but a product of a people who are comfortable in their own skins.

The North of Portugal confounds common British expectations in many ways.

Over here people are not really that dark skinned or that hot blooded.

Porto if anything is in reality a city of cool elegance and its people are on the whole very friendly and very relaxed. Indeed the overall vibe could be one of the most “chilled out”, if not the most, in the whole of Europe.

The people of the Algarve owe more of their genetic lineage to the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula and this shows in their faces and in their temperament.

In contrast, the cultural and genetic heritage of Porto is a classical European one, and Porto feels distinctly much more South West European than, say, a Madeira does for somewhat self-evident reasons.

In 2003 European Commission statisticians were said to have claimed that the UK was not an “island” – although it is (ironically) as possible that this story was an apocryphal manifestation of “little island” anxiety as it was of political pragmatism.

Any such claim seems far fetched in Brexit Britain because it ignores the psychological reality of British attitudes as much as it defies Britain’s physical geography.

Britain has a long and increasingly facile Modern history of misrepresenting the foreign.

Whereas this guilty masturbatory pleasure might in previous generations have taken aim at the Germans or the Portuguese, today it might take aim at the newer members of the European Union such as the Polish or the Romanians.

The concept of “saudade” has been lost on the British, as has the concept of an even smaller nation (than the UK) of 10 million people ruling the world 400 years ago as Portugal once did.

In the UK Jose Mourinho’s deep thinking passion for football was first mistaken for shallow arrogance.

In the UK the McCanns were first mistaken as the victims of Portuguese incompetence and lethargy.

But Brexit Britain should provide us with the impetus to rethink.

The Autumn 1956 edition of the Berry Bros and Rudd magazine article “Port: the Englishman’s wine” makes strange and perhaps uncomfortable reading in Brexit Britain. The article is sincere in its re-imagining and remaking of the importance of Britain because it is of its time, yet even “Port: the Englishman’s wine” begins with the sentence “Port is probably the only drink to owe its character entirely to international co-operation”.

It goes on to elaborate that “Port is the fruit of long-standing Anglo-Portuguese friendship, the Latin partner providing the right soil and climate for making the wine, the Anglo-Saxon the commercial initiative for its production and the ideal setting for its enjoyment.” before concluding, again somewhat illogically, that “Port is still known as “the Englishman’s wine”, and it would be a great loss to our heritage of good living if the wine that Professor Saintsbury described as being “in pre-established harmony with the best English character” were to be rated at less than its true worth by the post-war generation.”

It is time to rethink.

An entire body of serious academic thought has arisen today to question how the Harry Potter franchise quintessentially represented British culture to a foreign audience and tapped into the near universal commercial potential to export and sell a nostalgic (and now almost alternate) British identity by harnessing the power of British aesthetics in much the same way as period dramas and the British Royal Family do.

Locations from the films have since become tourism sites listed on the VisitBritain website.

But to what extent is the conception of Harry Potter as a wholly English creation mere fantasy?

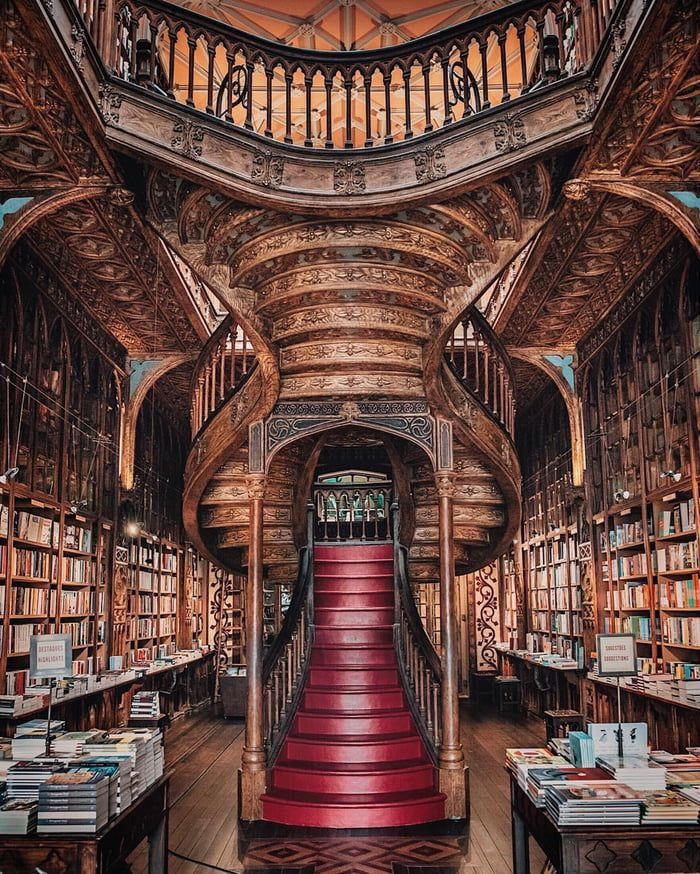

JK Rowling lived in Porto between 1991 and 1993 and was a frequent visitor of the Livraria Lello bookstore, a quite beautiful landmark and tourist hotspot of Porto.

In a 1 September 2008 Business Insider article by Harrison Jacobs, he writes “Many have suggested that the bookstore's ornate neo-Gothic architecture bears a striking resemblance to depictions of both Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, the central setting of the books, and the Flourish and Blotts bookshop, where characters in the books purchase their books on magic.”

As to the famed uniforms of the characters of Harry Potter, as a writer I believe that a single picture speaks a thousand words. One of the most striking sights in Porto is the black robes that the students of the University of Porto wear.

Whereas revelations such as these might interest someone on the British Left and induce tortured emotions of jealousy and shock amongst those on the British Right, it is important to understand that, as a very basic and uncontested historical fact, this process of cross-national symbiosis is as old as culture itself is.

I visited Sintra in the knowledge that it had been lived in by Lord Byron, one of the giants of British literary history, who immortalised the place, another Portuguese UNESCO World Heritage landscape, in his famous poem Childe Harolde's Pilgrimage: "Lo! Cintra's glorious Eden intervenes in variegated maze of mount and glen."

I visited Duino in Italy in the knowledge that Duino Castle had inspired the Duino Elegies by the poet Rainer Maria Rilke.

The “Berlin Trilogy” is widely regarded as the best work of David Bowie, one of my all time heroes.

When it comes to culture, man is a port more than he is an island.

There are those who do not understand this. And there are those with an education.